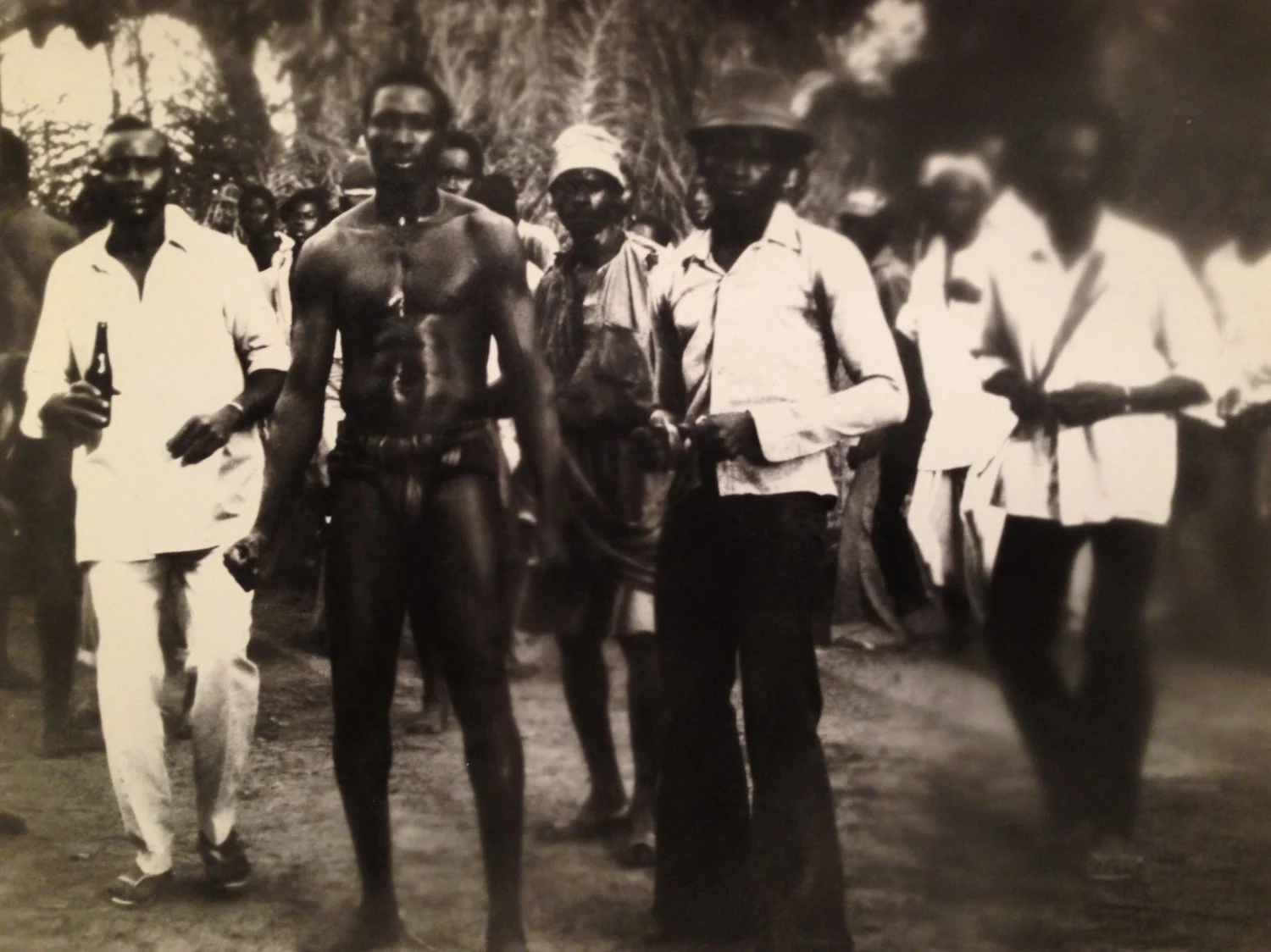

Okonkwo returns to Umuofia

seven years was a long time to be away from one’s clan,

but he would return to his fatherland and fan his fame—

a bush-fire beneath the stiff harmattan wind. he had a plan:

reclaim his land, rebuild his compound, regain his titles and place

among the egwugwu. but Okonkwo was not prepared

for what he found. his motherland was good to him in exile,

kind. but Mbanta was not filled with warriors. they were weak.

how else could they fall from the grand, old ways—the bonds

of kinship—and allow an abominable religion to fester

like an un-lanced boil or an untreated bout of iba? his Umuofia

was feared by her neighbors, known for her power in war

and in magic. her priests and medicine men possessing

the most potent rites and fetishes, the shrine of agadi-nwayi

among them. thus Okonkwo could not believe Obierika’s reports

of home. but by the second market week back, he began to see

the truth. how his brothers strut across the village square

in white shirts and dusky trousers, abandoning the loincloth

and wrappers worn since the founder of the clan engaged a spirit

of the wild for seven days and nights. how his kinsmen drink

palm wine tapped in Umuru from glass bottles, their gourds

and skulls gathering dust on their obi walls. how titled men

allow themselves to be dragged by kotma to the white man’s court,

to be beaten by his perverted justice. how even some elders dance

to the rhythm of the white man’s religion, deaf to the ekwe

and ogene talking across villages, across the clan’s history.

how supposed men stride—hatted heads held high—to and from

their abomination, their church, in the Evil Forest, believing

their Jesu Kristi will save them from the wrath of Ekwensu and Ani,

Amadiora and Chukwu. it was easier when the converts were only

efulefu—sheaths taken into battle, machetes forgotten at home,

the excrement of the clan lapped up by this mad-dog faith. but now

even Ogbuefis have severed their anklets, become as agbala, to join

the Christians’ meager feast of their god-man’s murdered body.

something must be done. but surrounded by so many such as these…

as cold water poured on a roaring fire, he stifles a sorrow, a grief

he has not known since the last days of the son whose name will not

be remembered in the clan and the one who will. his fist aches,

reflexively clenching around the machete resting inside his obi door.

he will shake out his smoked raffia shirt, examine his feathered headgear

and shield to satisfaction. he turns for home as if on springs, heels

hardly touching the ground. as the elders say,

whenever you see a toad jumping in broad daylight,

know that something is after its life.